Code

library(tidyverse)From messy CSVs to analysis-ready tables with tidyr and stringr

Noah Weidig

February 22, 2025

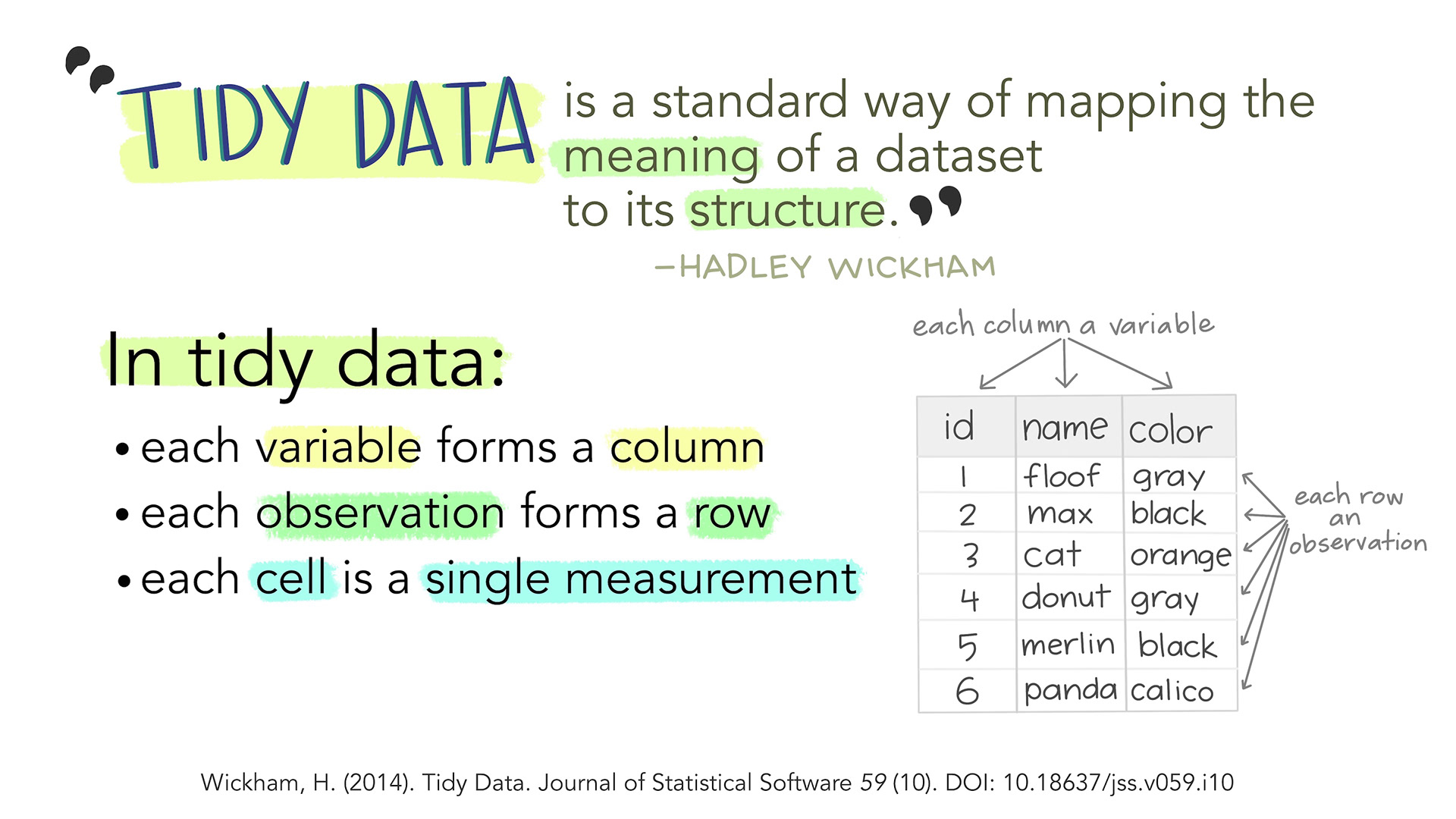

You know the drill. Someone hands you a spreadsheet with columns like cases_2019, cases_2020, cases_2021, values crammed into single cells, and mysterious NAs scattered everywhere. Before you can analyze anything, you need to clean it. This is where tidyr and stringr come in — and where most of your time as a data analyst actually goes.

This tutorial builds directly on Basics of dplyr. If you’re comfortable with filter(), mutate(), and the pipe, you’re ready.

We’ll use two built-in datasets throughout this post:

who2 — World Health Organization tuberculosis data (comes with tidyr). Wide, messy, and realistic.starwars — Character data from the Star Wars films (comes with dplyr). Has strings to clean and list-columns to untangle.# A tibble: 7,240 × 58

country year sp_m_014 sp_m_1524 sp_m_2534 sp_m_3544 sp_m_4554 sp_m_5564

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Afghanistan 1980 NA NA NA NA NA NA

2 Afghanistan 1981 NA NA NA NA NA NA

3 Afghanistan 1982 NA NA NA NA NA NA

4 Afghanistan 1983 NA NA NA NA NA NA

5 Afghanistan 1984 NA NA NA NA NA NA

6 Afghanistan 1985 NA NA NA NA NA NA

7 Afghanistan 1986 NA NA NA NA NA NA

8 Afghanistan 1987 NA NA NA NA NA NA

9 Afghanistan 1988 NA NA NA NA NA NA

10 Afghanistan 1989 NA NA NA NA NA NA

# ℹ 7,230 more rows

# ℹ 50 more variables: sp_m_65 <dbl>, sp_f_014 <dbl>, sp_f_1524 <dbl>,

# sp_f_2534 <dbl>, sp_f_3544 <dbl>, sp_f_4554 <dbl>, sp_f_5564 <dbl>,

# sp_f_65 <dbl>, sn_m_014 <dbl>, sn_m_1524 <dbl>, sn_m_2534 <dbl>,

# sn_m_3544 <dbl>, sn_m_4554 <dbl>, sn_m_5564 <dbl>, sn_m_65 <dbl>,

# sn_f_014 <dbl>, sn_f_1524 <dbl>, sn_f_2534 <dbl>, sn_f_3544 <dbl>,

# sn_f_4554 <dbl>, sn_f_5564 <dbl>, sn_f_65 <dbl>, ep_m_014 <dbl>, …# A tibble: 87 × 5

name height mass skin_color homeworld

<chr> <int> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

1 Luke Skywalker 172 77 fair Tatooine

2 C-3PO 167 75 gold Tatooine

3 R2-D2 96 32 white, blue Naboo

4 Darth Vader 202 136 white Tatooine

5 Leia Organa 150 49 light Alderaan

6 Owen Lars 178 120 light Tatooine

7 Beru Whitesun Lars 165 75 light Tatooine

8 R5-D4 97 32 white, red Tatooine

9 Biggs Darklighter 183 84 light Tatooine

10 Obi-Wan Kenobi 182 77 fair Stewjon

# ℹ 77 more rowsThe most common mess you’ll run into is data that’s wide when it should be long. The who2 dataset is a textbook example — it has separate columns for every combination of diagnosis method, sex, and age group.

[1] "country" "year" "sp_m_014" "sp_m_1524" "sp_m_2534" "sp_m_3544"

[7] "sp_m_4554" "sp_m_5564" "sp_m_65" "sp_f_014" "sp_f_1524" "sp_f_2534"

[13] "sp_f_3544" "sp_f_4554" "sp_f_5564" "sp_f_65" "sn_m_014" "sn_m_1524"

[19] "sn_m_2534" "sn_m_3544"Each of those sp_m_014, sp_f_1524 columns encodes three variables in a single column name. That’s not tidy. Let’s pivot.

# A tibble: 76,046 × 4

country year category count

<chr> <dbl> <chr> <dbl>

1 Afghanistan 1997 sp_m_014 0

2 Afghanistan 1997 sp_m_1524 10

3 Afghanistan 1997 sp_m_2534 6

4 Afghanistan 1997 sp_m_3544 3

5 Afghanistan 1997 sp_m_4554 5

6 Afghanistan 1997 sp_m_5564 2

7 Afghanistan 1997 sp_m_65 0

8 Afghanistan 1997 sp_f_014 5

9 Afghanistan 1997 sp_f_1524 38

10 Afghanistan 1997 sp_f_2534 36

# ℹ 76,036 more rowsThe values_drop_na = TRUE argument quietly drops all the rows where count is NA. Without it, you’d end up with thousands of empty rows — a common gotcha that balloons your data for no reason.

Those category values still pack three pieces of information into one string. We can split them during the pivot itself.

# A tibble: 76,046 × 6

country year diagnosis sex age_group count

<chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Afghanistan 1997 sp m 014 0

2 Afghanistan 1997 sp m 1524 10

3 Afghanistan 1997 sp m 2534 6

4 Afghanistan 1997 sp m 3544 3

5 Afghanistan 1997 sp m 4554 5

6 Afghanistan 1997 sp m 5564 2

7 Afghanistan 1997 sp m 65 0

8 Afghanistan 1997 sp f 014 5

9 Afghanistan 1997 sp f 1524 38

10 Afghanistan 1997 sp f 2534 36

# ℹ 76,036 more rowsOne call and we went from a 56-column mess to a clean, long-format table with clearly named variables. That’s the power of pivot_longer().

Sometimes you need the opposite — spreading long data into a wider format for summary tables or specific analyses. Let’s say we want a quick comparison table of total TB cases by diagnosis method and sex.

# A tibble: 4 × 3

diagnosis f m

<chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 ep 941880 1044299

2 rel 1201596 2018976

3 sn 2439139 3840388

4 sp 11324409 20586831pivot_wider() is the inverse of pivot_longer(). You’ll reach for it less often, but it’s essential for creating cross-tabulations and reporting tables.

Sometimes a single column contains multiple values separated by a delimiter. Let’s manufacture a quick example to see separate_wider_delim() in action.

# A tibble: 4 × 3

id country_code city

<int> <chr> <chr>

1 1 USA New York

2 2 CAN Toronto

3 3 GBR London

4 4 AUS Sydney This cleanly splits one column into two. If the number of pieces isn’t consistent across rows, use too_few and too_many to control the behavior:

# A tibble: 3 × 4

id first second third

<int> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 1 A B C

2 2 D E <NA>

3 3 F G H-I The too_few = "align_start" fills missing pieces with NA from the right. The too_many = "merge" lumps extra pieces into the last column. This keeps your pipeline from crashing on messy, inconsistent data.

unite() is the reverse — gluing columns together.

# A tibble: 6 × 5

country year diagnosis demographic count

<chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Afghanistan 1997 sp m_014 0

2 Afghanistan 1997 sp m_1524 10

3 Afghanistan 1997 sp m_2534 6

4 Afghanistan 1997 sp m_3544 3

5 Afghanistan 1997 sp m_4554 5

6 Afghanistan 1997 sp m_5564 2This is handy when you need to create an interaction label for plotting or joining.

Real-world data is full of inconsistent text. The stringr package gives you a consistent set of functions (all starting with str_) for detecting, extracting, and replacing patterns.

str_detect() returns TRUE or FALSE, making it perfect inside filter().

# A tibble: 3 × 14

name height mass hair_color skin_color eye_color birth_year sex gender

<chr> <int> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

1 Luke Sky… 172 77 blond fair blue 19 male mascu…

2 Anakin S… 188 84 blond fair blue 41.9 male mascu…

3 Shmi Sky… 163 NA black fair brown 72 fema… femin…

# ℹ 5 more variables: homeworld <chr>, species <chr>, films <list>,

# vehicles <list>, starships <list># A tibble: 14 × 2

name skin_color

<chr> <chr>

1 R2-D2 white, blue

2 R5-D4 white, red

3 Jabba Desilijic Tiure green-tan, brown

4 Watto blue, grey

5 Sebulba grey, red

6 Ratts Tyerel grey, blue

7 Dud Bolt blue, grey

8 Gasgano white, blue

9 Ben Quadinaros grey, green, yellow

10 Zam Wesell fair, green, yellow

11 R4-P17 silver, red

12 Wat Tambor green, grey

13 Shaak Ti red, blue, white

14 Grievous brown, white str_replace() swaps the first match; str_replace_all() swaps every match. This is essential for cleaning up inconsistent labels.

# A tibble: 14 × 2

name skin_color

<chr> <chr>

1 R2-D2 white/blue

2 R5-D4 white/red

3 Jabba Desilijic Tiure green-tan/brown

4 Watto blue/grey

5 Sebulba grey/red

6 Ratts Tyerel grey/blue

7 Dud Bolt blue/grey

8 Gasgano white/blue

9 Ben Quadinaros grey/green/yellow

10 Zam Wesell fair/green/yellow

11 R4-P17 silver/red

12 Wat Tambor green/grey

13 Shaak Ti red/blue/white

14 Grievous brown/white A common use case: standardizing messy category labels.

[1] "united states" "united states" "united states" "united states"

[5] "united states"str_extract() grabs the first matching portion of a string. Let’s pull the numeric age boundaries from our cleaned WHO data.

Whitespace is the silent killer of joins and group-bys. Two rows that look identical can fail to match because one has a trailing space.

[1] "Alice" "Bob" "Charlie" "Alice" [1] "too many spaces"Always trim your strings before joining or grouping. This one habit will save you hours of debugging.

When you read a CSV, character columns sometimes get read as factors. This means levels() bakes in the exact set of unique values. If you then filter() down to a subset, the unused levels stick around as ghosts — inflating your legend in plots, adding empty groups in summaries, and generally causing confusion.

[1] "bird" "cat" "dog" [1] "cat" "dog"The lesson: use droplevels() after filtering factor data, or better yet, keep text as character columns with stringsAsFactors = FALSE (the default since R 4.0) and convert to factors only when you need explicit ordering.

Missing values propagate silently. Any arithmetic with NA returns NA. Any comparison with NA returns NA. This means filter(x == NA) never returns rows — use is.na() instead.

[1] 0# A tibble: 6 × 2

name mass

<chr> <dbl>

1 Wilhuff Tarkin NA

2 Mon Mothma NA

3 Arvel Crynyd NA

4 Finis Valorum NA

5 Rugor Nass NA

6 Ric Olié NAFor summaries, always pass na.rm = TRUE.

# A tibble: 1 × 1

avg_height

<dbl>

1 NA# A tibble: 1 × 1

avg_height

<dbl>

1 175.If you want to replace NAs with a default value, use replace_na() from tidyr.

Before any analysis, always check for duplicates. distinct() keeps unique rows, and get_dupes() from the janitor package can identify which rows are repeated. Here’s the tidyverse approach:

[1] 0Zero duplicates — good. When you do find them, decide whether to keep the first, last, or aggregate.

Let’s chain everything into a real pipeline. Starting from the raw who2 data, we’ll clean, reshape, and summarize in one shot.

who2 |>

# Reshape: wide to long, splitting column names

pivot_longer(

cols = !c(country, year),

names_to = c("diagnosis", "sex", "age_group"),

names_sep = "_",

values_to = "count",

values_drop_na = TRUE

) |>

# Clean: standardize sex labels

mutate(

sex = str_replace_all(sex, c("m" = "male", "f" = "female")),

age_start = str_extract(age_group, "^\\d+") |> as.integer()

) |>

# Filter: focus on recent data

filter(year >= 2010) |>

# Summarize: total cases by country and sex

group_by(country, sex) |>

summarize(total_cases = sum(count), .groups = "drop") |>

# Reshape: make a comparison table

pivot_wider(names_from = sex, values_from = total_cases) |>

# Sort: highest total burden first

mutate(total = male + female) |>

arrange(desc(total)) |>

head(10)# A tibble: 10 × 4

country female male total

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 China 1059090 2381098 3440188

2 India 585702 1316362 1902064

3 South Africa 593847 669632 1263479

4 Indonesia 530997 727340 1258337

5 Bangladesh 243335 399146 642481

6 Pakistan 206403 206493 412896

7 Russian Federation 121867 273245 395112

8 Philippines 111062 262920 373982

9 Democratic People's Republic of Korea 130943 211636 342579

10 Kenya 137336 188480 325816That’s eight operations piped together, and every step reads like a sentence. This kind of pipeline is what your daily R work will actually look like.

| Function | Package | What it does |

|---|---|---|

pivot_longer() |

tidyr | Reshape wide data to long format |

pivot_wider() |

tidyr | Reshape long data to wide format |

separate_wider_delim() |

tidyr | Split one column into many by delimiter |

unite() |

tidyr | Combine multiple columns into one |

replace_na() |

tidyr | Replace NA with a specified value |

str_detect() |

stringr | Test if a pattern exists in a string |

str_replace() |

stringr | Replace first match of a pattern |

str_replace_all() |

stringr | Replace all matches of a pattern |

str_extract() |

stringr | Pull out the first match of a pattern |

str_trim() |

stringr | Remove leading/trailing whitespace |

str_squish() |

stringr | Trim + collapse internal whitespace |

This is the unglamorous core of data analysis — the cleaning that happens before any chart or model. Master these tools and you’ll spend less time fighting your data and more time learning from it.

---

title: "Data Cleaning in the Real World"

subtitle: "From messy CSVs to analysis-ready tables with tidyr and stringr"

execute:

warning: false

author: "Noah Weidig"

date: "2025-02-22"

categories: [code, tidyverse]

image: "images/tidyr.jpg"

description: "Learn how to reshape, split, and clean messy data using tidyr and stringr — pivoting, separating columns, pattern matching, and handling common gotchas."

toc: true

toc-depth: 2

code-fold: show

---

[](https://twitter.com/allison_horst)

You know the drill. Someone hands you a spreadsheet with columns like `cases_2019`, `cases_2020`, `cases_2021`, values crammed into single cells, and mysterious `NA`s scattered everywhere. Before you can analyze anything, you need to *clean* it. This is where `tidyr` and `stringr` come in — and where most of your time as a data analyst actually goes.

This tutorial builds directly on [Basics of dplyr](../dplyr-basics/index.qmd). If you're comfortable with `filter()`, `mutate()`, and the pipe, you're ready.

# Setup

```{r}

library(tidyverse)

```

We'll use two built-in datasets throughout this post:

- **`who2`** — World Health Organization tuberculosis data (comes with `tidyr`). Wide, messy, and realistic.

- **`starwars`** — Character data from the Star Wars films (comes with `dplyr`). Has strings to clean and list-columns to untangle.

```{r}

who2

```

```{r}

starwars |> select(name, height, mass, skin_color, homeworld)

```

# Reshaping with pivot_longer()

The most common mess you'll run into is data that's *wide* when it should be *long*. The `who2` dataset is a textbook example — it has separate columns for every combination of diagnosis method, sex, and age group.

```{r}

who2 |> colnames() |> head(20)

```

Each of those `sp_m_014`, `sp_f_1524` columns encodes three variables in a single column name. That's not tidy. Let's pivot.

```{r}

who_long <- who2 |>

pivot_longer(

cols = !c(country, year),

names_to = "category",

values_to = "count",

values_drop_na = TRUE

)

who_long

```

The `values_drop_na = TRUE` argument quietly drops all the rows where count is `NA`. Without it, you'd end up with thousands of empty rows — a common gotcha that balloons your data for no reason.

## Pivoting with names_sep

Those `category` values still pack three pieces of information into one string. We can split them during the pivot itself.

```{r}

who_tidy <- who2 |>

pivot_longer(

cols = !c(country, year),

names_to = c("diagnosis", "sex", "age_group"),

names_sep = "_",

values_to = "count",

values_drop_na = TRUE

)

who_tidy

```

One call and we went from a 56-column mess to a clean, long-format table with clearly named variables. That's the power of `pivot_longer()`.

# Going wide with pivot_wider()

Sometimes you need the opposite — spreading long data into a wider format for summary tables or specific analyses. Let's say we want a quick comparison table of total TB cases by diagnosis method and sex.

```{r}

who_tidy |>

group_by(diagnosis, sex) |>

summarize(total = sum(count), .groups = "drop") |>

pivot_wider(

names_from = sex,

values_from = total

)

```

`pivot_wider()` is the inverse of `pivot_longer()`. You'll reach for it less often, but it's essential for creating cross-tabulations and reporting tables.

# Splitting and combining columns

## separate_wider_delim()

Sometimes a single column contains multiple values separated by a delimiter. Let's manufacture a quick example to see `separate_wider_delim()` in action.

```{r}

messy_locations <- tibble(

id = 1:4,

location = c("USA-New York", "CAN-Toronto", "GBR-London", "AUS-Sydney")

)

messy_locations |>

separate_wider_delim(

location,

delim = "-",

names = c("country_code", "city")

)

```

This cleanly splits one column into two. If the number of pieces isn't consistent across rows, use `too_few` and `too_many` to control the behavior:

```{r}

tricky <- tibble(

id = 1:3,

value = c("A-B-C", "D-E", "F-G-H-I")

)

tricky |>

separate_wider_delim(

value,

delim = "-",

names = c("first", "second", "third"),

too_few = "align_start",

too_many = "merge"

)

```

The `too_few = "align_start"` fills missing pieces with `NA` from the right. The `too_many = "merge"` lumps extra pieces into the last column. This keeps your pipeline from crashing on messy, inconsistent data.

## unite()

`unite()` is the reverse — gluing columns together.

```{r}

who_tidy |>

unite("demographic", sex, age_group, sep = "_") |>

select(country, year, diagnosis, demographic, count) |>

head()

```

This is handy when you need to create an interaction label for plotting or joining.

# String manipulation with stringr

Real-world data is full of inconsistent text. The `stringr` package gives you a consistent set of functions (all starting with `str_`) for detecting, extracting, and replacing patterns.

## str_detect() — finding patterns

`str_detect()` returns `TRUE` or `FALSE`, making it perfect inside `filter()`.

```{r}

# Which Star Wars characters have "Skywalker" in their name?

starwars |>

filter(str_detect(name, "Skywalker"))

```

```{r}

# Find characters with multiple skin colors (contain a comma)

starwars |>

filter(str_detect(skin_color, ",")) |>

select(name, skin_color)

```

## str_replace() and str_replace_all()

`str_replace()` swaps the first match; `str_replace_all()` swaps every match. This is essential for cleaning up inconsistent labels.

```{r}

starwars |>

mutate(skin_color = str_replace_all(skin_color, ", ", "/")) |>

filter(str_detect(skin_color, "/")) |>

select(name, skin_color)

```

A common use case: standardizing messy category labels.

```{r}

raw_labels <- c("United States", "united states", "US", "U.S.", "usa")

raw_labels |>

str_to_lower() |>

str_replace_all(c(

"^us$" = "united states",

"^u\\.s\\.$" = "united states",

"^usa$" = "united states"

))

```

## str_extract() — pulling out pieces

`str_extract()` grabs the first matching portion of a string. Let's pull the numeric age boundaries from our cleaned WHO data.

```{r}

who_tidy |>

mutate(

age_start = str_extract(age_group, "^\\d+") |> as.integer()

) |>

distinct(age_group, age_start) |>

arrange(age_start)

```

## str_trim() and str_squish()

Whitespace is the silent killer of joins and group-bys. Two rows that *look* identical can fail to match because one has a trailing space.

```{r}

messy_names <- c(" Alice ", "Bob", " Charlie ", " Alice")

# str_trim removes leading/trailing whitespace

str_trim(messy_names)

# str_squish also collapses internal whitespace

str_squish(" too many spaces ")

```

Always trim your strings before joining or grouping. This one habit will save you hours of debugging.

# Common gotchas

## Factor explosions

When you read a CSV, character columns sometimes get read as factors. This means `levels()` bakes in the exact set of unique values. If you then `filter()` down to a subset, the unused levels stick around as ghosts — inflating your legend in plots, adding empty groups in summaries, and generally causing confusion.

```{r}

# Simulate the problem

species_factor <- factor(c("cat", "dog", "bird", "cat", "dog"))

filtered <- species_factor[species_factor != "bird"]

# "bird" is gone from the data but still in the levels

levels(filtered)

# Fix: drop unused levels

levels(droplevels(filtered))

```

The lesson: use `droplevels()` after filtering factor data, or better yet, keep text as character columns with `stringsAsFactors = FALSE` (the default since R 4.0) and convert to factors only when you need explicit ordering.

## NA handling

Missing values propagate silently. Any arithmetic with `NA` returns `NA`. Any comparison with `NA` returns `NA`. This means `filter(x == NA)` never returns rows — use `is.na()` instead.

```{r}

# This returns nothing — NA == NA is NA, not TRUE

starwars |>

filter(mass == NA) |>

nrow()

# This is what you actually want

starwars |>

filter(is.na(mass)) |>

select(name, mass) |>

head()

```

For summaries, always pass `na.rm = TRUE`.

```{r}

# Without na.rm — returns NA

starwars |>

summarize(avg_height = mean(height))

# With na.rm — returns the actual mean

starwars |>

summarize(avg_height = mean(height, na.rm = TRUE))

```

If you want to replace `NA`s with a default value, use `replace_na()` from tidyr.

```{r}

starwars |>

mutate(hair_color = replace_na(hair_color, "unknown")) |>

count(hair_color, sort = TRUE) |>

head()

```

## Duplicate rows

Before any analysis, always check for duplicates. `distinct()` keeps unique rows, and `get_dupes()` from the `janitor` package can identify which rows are repeated. Here's the tidyverse approach:

```{r}

who_tidy |>

group_by(country, year, diagnosis, sex, age_group) |>

filter(n() > 1) |>

nrow()

```

Zero duplicates — good. When you do find them, decide whether to keep the first, last, or aggregate.

# Putting it all together

Let's chain everything into a real pipeline. Starting from the raw `who2` data, we'll clean, reshape, and summarize in one shot.

```{r}

who2 |>

# Reshape: wide to long, splitting column names

pivot_longer(

cols = !c(country, year),

names_to = c("diagnosis", "sex", "age_group"),

names_sep = "_",

values_to = "count",

values_drop_na = TRUE

) |>

# Clean: standardize sex labels

mutate(

sex = str_replace_all(sex, c("m" = "male", "f" = "female")),

age_start = str_extract(age_group, "^\\d+") |> as.integer()

) |>

# Filter: focus on recent data

filter(year >= 2010) |>

# Summarize: total cases by country and sex

group_by(country, sex) |>

summarize(total_cases = sum(count), .groups = "drop") |>

# Reshape: make a comparison table

pivot_wider(names_from = sex, values_from = total_cases) |>

# Sort: highest total burden first

mutate(total = male + female) |>

arrange(desc(total)) |>

head(10)

```

That's eight operations piped together, and every step reads like a sentence. This kind of pipeline is what your daily R work will actually look like.

# Quick reference

| Function | Package | What it does |

|----------|---------|-------------|

| `pivot_longer()` | tidyr | Reshape wide data to long format |

| `pivot_wider()` | tidyr | Reshape long data to wide format |

| `separate_wider_delim()` | tidyr | Split one column into many by delimiter |

| `unite()` | tidyr | Combine multiple columns into one |

| `replace_na()` | tidyr | Replace `NA` with a specified value |

| `str_detect()` | stringr | Test if a pattern exists in a string |

| `str_replace()` | stringr | Replace first match of a pattern |

| `str_replace_all()` | stringr | Replace all matches of a pattern |

| `str_extract()` | stringr | Pull out the first match of a pattern |

| `str_trim()` | stringr | Remove leading/trailing whitespace |

| `str_squish()` | stringr | Trim + collapse internal whitespace |

This is the unglamorous core of data analysis — the cleaning that happens before any chart or model. Master these tools and you'll spend less time fighting your data and more time learning from it.